Red Cross Arts and Skills

- Liz Schott

- Feb 16, 2025

- 7 min read

Updated: Mar 11, 2025

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, Liebes was sickened by the United States’s internment of Japanese American citizens. Simultaneously, she was worried about the effect the war would have on her business, concerned that textiles would be considered a frivolity in these dire days. She sought ways to channel these parallel emotions, and was soon rewarded with a phone call that changed her life.

Liebes’s exposure at the Golden Gate International Exposition resulted in her receiving queries from artists from across the country and creative spectrum, asking how they could help with the war effort.

So, when the Red Cross asked Liebes in 1942 to help wounded veterans returning from WWII, despite the promise of massive amounts of work, Liebes was quick to say yes. Her patriotism, connections, and work ethic were exactly what the times needed.

She wrote: “... a telephone call presented me with a wonderful opportunity to put my experience to work in the war. What followed enriched my life as few other events ever could do. The hospitals on the Atlantic Coast were overflowing with casualties.”

The caller, Helen Cutting, had converted her own home into a convalescent hospital. She said to Liebes, “I know about your work as a weaver . . . and I wonder if you think it would be practical to try to teach convalescents to weave?”

Liebes enthusiastically responded in the affirmative. She always contended that a ten-year-old could learn to weave. It was finding the right looms that concerned her.

“In the original discussion [with Helen Cutting], I told her the first problem would be to find looms small enough to fit on the sides of a hospital bed or perhaps on a tray placed across the area of a wheelchair. Looms of ordinary sizes could be used for ambulatory cases and men capable of working at a table.”

And, with that, Liebes couldn’t help herself and her busy mind. She started rattling off several other arts and skills that could be taught to the servicemen and women. Helen Cutting seized her opportunity:

Cutting told Liebes, “‘I think you’re just the one to head up this project on the Pacific Coast. How about it?’

Liebes wrote: If I could have foreseen the consequences of this proposal, the thousands of hours of traveling, walking my legs off in hospitals, and that awful bugbear, making speeches, I might have hesitated.”

Instead, she got the old bait and switch.

“ . . . I was given the title of National Art Director, not just for the Pacific hospitals. I went flea-hopping all over the country, conferring with the heads of hospitals, recruiting artists and craftsmen, and appealing for equipment.”

If only she’d known about the Structo loom, she might have gotten away with a more manageable role!

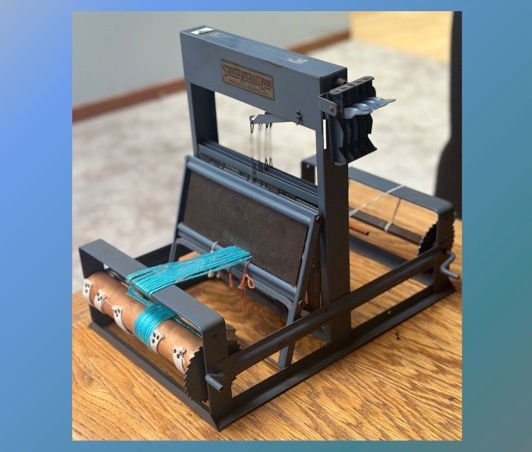

Liebes wrote: “My special interest, of course, was in weaving. Small looms, 10 inches wide, eventually became available for Arts and Skills. These were “Structo” looms, that is without the treadles normally operated by the weaver’s feet; a lever on the side changed the warp. These were placed across a bed, resting on the sides, or on the arms of a wheelchair. Sears Roebuck donated 10,000 of these looms to us and I signed a check for 10,000 more, but we never had enough, which gives some indication of the number of disabled men who learned to weave in the hospitals. Weaving is a great tranquilizer. The effect can be almost hypnotic. It seemed to have a special value in treating men suffering from battle fatigue and shattered nerves. Usually, they began by playing with the loom, like a toy, but the more they discovered its uses, the more interested they became.”

Liebes traveled constantly on behalf of Arts and Skills, even returning to her native Santa Rosa to appeal for support. She visited Letterman in San Francisco, Mare Island in Vallejo, Fitzsimmons General in Denver, Great Lakes in Chicago, Massachusetts General in Boston, Halloran in New York and St. Elizabeth’s in Washington. Over 120 hospitals across the country had Arts & Skills programs.

She wrote: “I particularly enjoyed seeing the men working in the sunshine in a craft shop on the roof of an old hospital on the corner of Van Ness and Pacific Avenue in San Francisco.”

These were the objectives for the weaving program, but would very easily have translated to all of the arts and skills.

“The objectives,” Liebes wrote, “are very simple. First the overall one of dispelling boredom . . . and to give the men something to think about. Second, from the psychological point of view, keeping work patterns alive . . . The whole point of view is, “You have lost an arm, a leg? That’s just too bad, but still you can take your place in society as a perfectly self-respecting, wage-earning individual.”

This was not pure rhetoric coming from Liebes. When her father was 13 years old, he lost his right arm in a hunting accident. While hunting rabbits, his gun fired when he was crawling under a fence. His right arm and shoulder were mangled. His parents transported him 12 miles to Santa Rosa by horse and buggy, and the boy lost “an enormous quantity of blood.” His arm was amputated immediately to save his life.

Liebes’s father never talked about the accident. She wrote, “ . . his determination to overcome his handicap, to do for himself in all things, to ask no quarter from life, made a deep and indelible impression on me.”

It is this impression that allowed her to contend that it was just “too bad” if you lost a limb in the war.

She wrote: “Struggle was the inexorable law of life and if I fought hard enough, as my father did, success could be expected. Many times, frustrated and angry in the face of some problem, the memory of his grim persistence spurred me on to make another attempt. I have had failures, but never for want of trying just once more.”

Items the veterans made were exhibited all over the country, in part to motivate more soldiers to participate, and in part to generate publicity, and, therefore, public interest, in the program.

Twenty-eight different projects were offered, ranging from wood carving to fly tying to fingerpainting to, of course, weaving.

There were standards established for Arts and Skills volunteer teachers.

Liebes recalled: “ . . . we drafted a rigid set of qualifications for for all the volunteers, artists, craftsmen, technicians [and] supervisors. A man might be thoroughly expert in his field but incapable of teaching others. A woman, genuinely eager to serve, might be temperamentally unsuited to function in an atmosphere of suffering, unable to bear the sight of horrible burns and men without arms and legs. All volunteers were carefully screened. The standard called for five qualifications, “knowledge of one or more arts and skills, teaching ability, desirable personality, sufficient time to devote to the Service, and cheerful acceptance of assignments, directions, and supervision.”

Sophie Kent, a well-connected friend of Liebes’s from San Francisco who headed up the volunteers in that city wrote: “A weaver at Letterman was sent into a ward with several bed looms. She found all the beds empty and a poker game going on at the end of the ward. She was slightly baffled to find, as she called the roll from her list; . . .those who were present insisted to a man that they were leaving the next day. Finally she came to the ‘W’s. “Witherspoon,” she read aloud. “Witherspoon? That’s an interesting name.” There was no answer.

She finished the list and turned to go, saying pleasantly, “Well, I guess nobody wants to weave today.” As she was going out the door, a man touched her on the arm. “I’m Witherspoon,” he said, “and I would like a loom.” Instantly three other men left the poker game. “We’ll take looms,” they said.

When the volunteer returned the next day, there were seven men waiting for her who also wanted looms . . ..”

Liebes recalled: “A typical example was the swarthy, tough-looking Marine who was weaving a piece of cloth with a bright blue and yellow design. Making the rounds in a ward, I saw it and commented, ‘That would make a pretty scarf for a girl.”

He looked surprised. ‘Yeah? You mean I could make something out of this? I thought it was just for fun.’

‘A woman could use it for a pillow covering, a table mat, material for a handbag, any number of things.’

For a moment, he was silent, thinking. Then he said, ‘My girl’s good at sewing. Can I send it home to her and tell her what you said?’

‘Of course,’ I said. ‘You made it.’

He smiled, a great sunburst of a smile. ‘I’m going to tell my girl to make herself a scarf, then I’m going to weave some more for my ma and my sisters and everyone I can think of. How about that?’

There were times when I had to walk away quickly, blinking back the tears. This was one of many.”

Well deserved appreciation and recognition came Liebes’s way at the conclusion of her service. She wrote often of being “heart and soul” for Arts & Skills, spending countless hours working for the unit even after her official resignation.

Signed by Harry Truman, Liebes’s certificate reads, “In recognition of meritorious personal service performed in behalf of the nation, her armed forces, and suffering humanity in the Second World War.”

Many alumni of the Arts and Skills came to visit Liebes over the years. She tried to see as many as she could, but had to call it quits when it the time commitment adversely impacted her work. One visitor, however, brought along samples of his weaving and design sketches that were so impressive, Liebes was persuaded by an employee to take a look. In walked Daren Pierce, who had learned to weave while recuperating from rheumatic fever at Mare Island during the war. Liebes hired him on the spot and he stayed with her for several years. He later became a partner at William Pahlmann Associates and a “much sought-after designer of interiors.”

What captured Liebes’s imagination more than his weaving were Pierce’s fashion sketches. But that’s a subject for another blog post.

Comments